West African masks are among the most iconic and culturally significant artifacts of African art. For centuries, these masks have played a vital role in the spiritual, social, and aesthetic life of numerous West African societies. Created mostly by hand, West African masks are used in various ceremonies and rituals, serving as powerful tools for communication between the material and spiritual worlds. Their unique forms, materials, and meanings make them a subject of fascination for both scholars and art enthusiasts globally.

Appearance and Distinctive Features

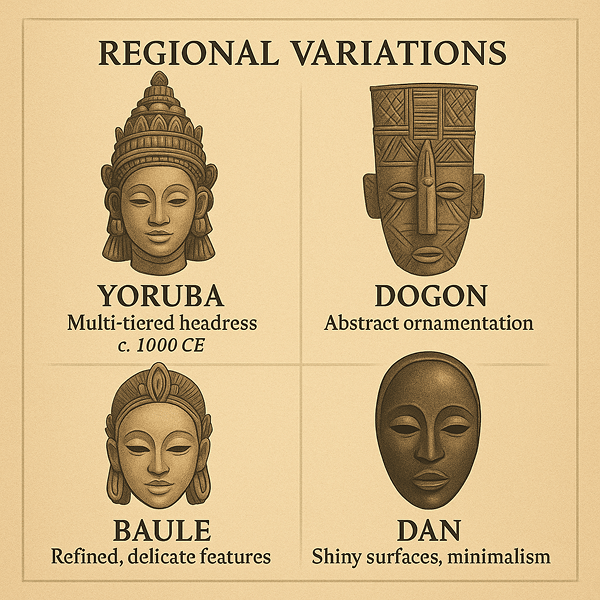

West African masks exhibit a wide range of forms and styles, reflecting the region’s diverse cultures and artistic traditions. Many masks have highly stylized human or animal faces, with elongated noses, protruding lips, or large almond-shaped eyes. Geometric patterns, bright pigments, feathers, shells, and beads enhance their visual impact. Some are painted with natural dyes, while others are adorned with raffia, metal, or animal skins. These masks are associated with groups such as the Yoruba (Nigeria), Dogon (Mali), Baule (Côte d’Ivoire), Senufo (Mali and Côte d’Ivoire), and Dan (Liberia and Côte d’Ivoire). The tradition of mask-making dates back at least a millennium, with evidence from Nok and Ife cultures.

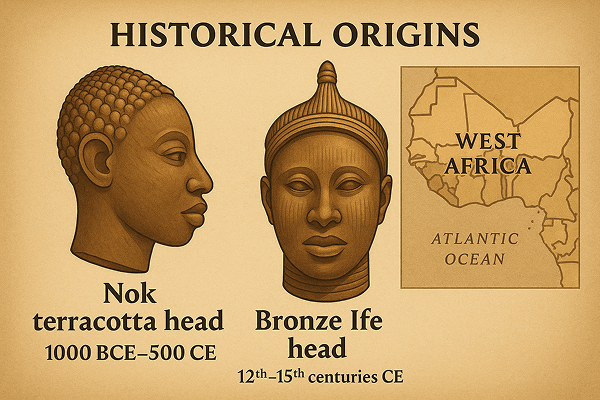

Historical Origins

The tradition of mask-making in West Africa is rooted in antiquity and reflects the region’s complex social, spiritual, and artistic evolution. Masks first appeared as societies expanded and religious rituals became more sophisticated, requiring representations of spirits, ancestors, or deities. The English word “mask” is derived from the Arabic “maskhara,” meaning “to ridicule” or “to transform,” highlighting the transformative functions of masks in ritual and performance. Over time, mask-making evolved alongside shifts in political organization, spiritual beliefs, and artistic innovation. As kingdoms and chiefdoms developed, masks became central to religious ceremonies and social hierarchy. Early masks were likely simple, but their designs became more elaborate as new materials, techniques, and motifs were adopted through trade and migration.

Archaeological finds such as Nok terracotta heads (1000 BCE–500 CE) and bronze Ife heads (12th–15th centuries CE) provide evidence of a long-standing tradition and the sophistication of West African art.

Cultural Significance and Symbolism

West African masks are far more than decorative objects; they are dynamic embodiments of cultural identity, spiritual beliefs, and communal values. Masks are deeply symbolic, often representing ancestors, spirits, animals, or mythological beings. Their meanings vary by culture but commonly embody protective, fertility, or ancestral powers. Used in religious rituals, masks serve as mediators between the human world and the supernatural. The wearer is believed to be transformed, temporarily becoming the spirit or entity represented. Myths often attribute the origins of masks to divine revelation or ancestral wisdom, and in some cultures, only select individuals can craft or wear them, emphasizing the sacred nature of the process. Masks play a central role in community life, marking events such as initiations, funerals, harvest festivals, and dispute settlements, while performances reinforce social norms and unite the community.

Materials and Crafting Techniques

The creation of West African masks is a highly skilled process, combining artistry, craftsmanship, and spiritual reverence. The primary material is wood, valued for its spiritual associations, but artisans also use raffia, animal skins, metal, cloth, beads, cowrie shells, and natural pigments. The crafting process is often surrounded by ritual and secrecy, beginning with the selection of a spiritually significant tree. Tools such as adzes, knives, chisels, and files are used for carving, sanding, and decoration. Techniques include carving, incising, painting, and inlaying with shells or beads. Some masks are adorned with feathers, horns, or textiles for added symbolic power. Distinctive regional styles are evident: Dogon masks feature angular forms and complex symbolism; Yoruba masks often have elaborate headdresses; Dan masks are known for their smooth, oval shapes. Color choices carry symbolic meaning — for example, white for purity or spirits, red for vitality, and black for the unknown or ancestral realm.

Functions and Uses

The role of masks in West African societies extends far beyond artistic expression. Masks are essential in rituals marking transitions such as birth, adulthood, marriage, and death, often serving as vehicles for spiritual possession and communication with ancestors or spirits. Masks are also used in theatrical performances, storytelling, and dance, serving not only as entertainment but also as moral instruction and historical recollection. Annual festivals and communal celebrations, such as the Yoruba Gelede festival or Dan masquerades, feature masks as central elements, fostering community identity and reinforcing tradition. While traditional uses persist, the production of masks for sale to tourists or display in art galleries has led to new forms and hybrid designs. Today, masks are used in contemporary art, performances, and even fashion, reflecting the ongoing vitality and adaptability of the tradition.

Regional Variations

West African masks are renowned for their extraordinary diversity, with each ethnic group contributing unique styles and symbolic meanings. Yoruba masks often have multi-tiered headdresses and bright colors, reflecting both artistic sophistication and spiritual significance. Dogon masks are known for their abstract shapes and spiritual complexity, frequently used in elaborate rituals. Baule masks feature refined, delicate forms and detailed ornamentation, often representing spirits of the bush and ancestral beings. Dan masks are recognized by their shiny surfaces and minimalist designs, symbolizing beauty and social harmony.

Some masks are exclusive to secret societies or specific age groups, while others are used only during particular seasons or events. Strict traditions often govern who may carve, wear, or even view certain masks, reinforcing their importance in social and spiritual life. While mask-making traditions also exist in Central and East Africa, West African masks are especially noted for their communal ritual roles and symbolic complexity. Unlike the death masks of ancient Egypt or the theatrical masks of Greece, West African masks are living, active participants in community life.

Famous Examples and Collections

Throughout history, certain West African masks have become celebrated for their artistry and cultural significance. Some of the most famous examples include Yoruba Gelede masks, Dogon Kanaga masks, Senufo Kpeliye masks, and Baule Goli masks, each recognized for its distinctive style and important role in its native culture. Leading museums around the world have assembled major collections of West African masks, including the British Museum (London), Musée du quai Branly (Paris), Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York), and the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art (Washington, D.C.). Archaeological discoveries, such as Nok terracottas and Ife bronzes, highlight the antiquity and sophistication of African mask-making. Private collectors and specialized galleries, as well as online platforms like toddmasks.com, play a vital role in preserving and showcasing these cultural treasures.

Influence on Art and Culture

The artistic and cultural influence of West African masks extends far beyond Africa. Their forms, motifs, and meanings have inspired creativity in modern art, notably influencing artists like Picasso, Matisse, and Modigliani. Masks frequently appear in literature, film, and music, symbolizing identity, transformation, and the dialogue between tradition and modernity. Contemporary designers and architects draw on mask motifs, using bold patterns and colors to evoke Africa’s artistic legacy. Masks are also central to efforts to preserve and revitalize African heritage, serving as symbols of identity and continuity, with their continued use in rituals and festivals transmitting traditional values to new generations.

Contemporary Status and Tradition Preservation

Today, mask-making remains vibrant and dynamic. Across West Africa, skilled artisans and apprentices maintain the craft, often blending traditional techniques with modern innovation. Workshops, festivals, and educational programs play a critical role in passing on mask-making knowledge, often supported by cultural organizations and museums. Some contemporary artists create masks intended as artworks, while others adapt traditional forms for galleries or performances, ensuring the tradition remains living and dynamic. Educational programs and hands-on master classes for locals and visitors help cultivate new generations of artisans and enthusiasts, sustaining the tradition into the future.

Collecting and Acquisition

The collecting of West African masks attracts scholars, art lovers, and cultural institutions worldwide. There is a thriving global market for authentic masks, with examples available at auctions, galleries, and reputable online platforms such as toddmasks.com. The value of a mask depends on its age, origin, rarity, condition, and whether it has been used in rituals. Masks with well-documented provenance and ceremonial history are particularly prized. Collectors should seek expert evaluation and provenance documentation, and consider the ethical implications of acquisition, supporting responsible dealers and ensuring that purchases benefit local communities and preserve cultural heritage.

West African masks are powerful testaments to the creativity, spirituality, and resilience of African societies. Their rich history, complex symbolism, and enduring relevance continue to captivate and educate people around the world. As these traditions evolve, striking a balance between innovation and respect for their deep meanings is essential. Through education, responsible collecting, and ongoing cultural exchange, the legacy of West African masks will remain vibrant for generations to come.