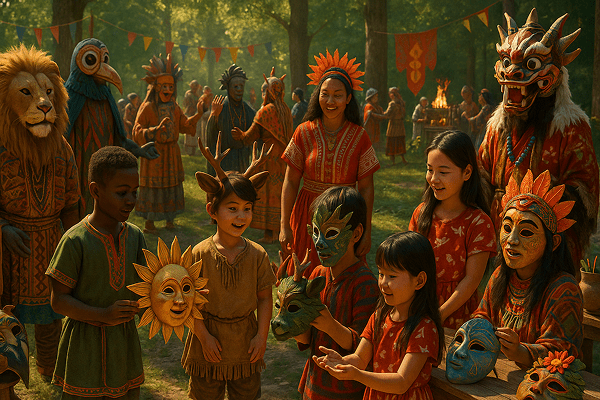

Seasonal Ceremony Masks are some of the most visually captivating and culturally rich artifacts found in communities across the globe. These masks are created and worn to mark important moments in the annual cycle — such as harvests, solstices, planting seasons, and New Year rites. Characterized by motifs that evoke nature, fertility, the elements, or ancestral spirits, Seasonal Ceremony Masks may feature animal faces, sunbursts, leaves, snowflakes, or mythological figures. They are often made with vibrant colors, natural materials, and elaborate decorations, serving as both protective charms and celebratory art. While their roots span Africa, Asia, the Americas, and Europe, these masks continue to be reimagined in modern festivals, eco-rituals, and art installations. For a broader look at festival mask traditions, see also Festival Ceremony Masks on toddmasks.com.

Historical Origins of Seasonal Ceremony Masks

The origins of Seasonal Ceremony Masks trace back to humanity’s earliest attempts to understand and influence the cycles of nature. The word “seasonal” refers to events recurring in a regular yearly pattern, while “ceremony” and “mask” derive from Latin terms for sacred rites and spirits. In ancient Egypt, Greece, China, and the Americas, masks played a role in rituals that honored the sun, moon, rain, or fertility gods, ensuring successful harvests and community well-being.

Over time, these masks evolved in response to changing religious beliefs, agricultural practices, and social structures. In many Indigenous societies, seasonal masks became central to ceremonies marking the passage from one time of year to another — such as the Hopi Kachina dances, Japanese New Year festivals, or European mummers’ plays. Historic artifacts, including Inuit shamanic masks, Slavic winter festival masks, and African harvest masks, are now preserved in museums and ethnographic collections worldwide.

Cultural Significance and Symbolism of Seasonal Ceremony Masks

Seasonal Ceremony Masks are deeply symbolic, representing the forces of nature, the spirits of ancestors, and the mysteries of life and death. In many cultures, masks are believed to channel the power of the seasons — to bring rain, fertility, or protection against calamity. They serve as intermediaries between the human and spirit worlds, helping communities to navigate uncertainty and change.

Spiritually, these masks may represent gods, mythical animals, or personified elements such as the sun, wind, or earth. Myths and legends abound — such as the Japanese tale of the Otafuku (Goddess of Mirth) mask bringing good fortune at New Year, or the West African story of animal masks mediating between humans and the land. Socially, masks reinforce communal identity, teach moral lessons, and celebrate the interconnectedness of people and the environment.

Materials and Crafting Techniques of Seasonal Ceremony Masks

Traditional Seasonal Ceremony Masks are made from natural, locally sourced materials, reflecting the connection to the earth and the changing seasons. Common materials include:

- Carved wood (cedar, balsa, oak, or native species)

- Plant fibers, leaves, grasses, and bark

- Animal hides, feathers, shells, and bone

- Clay, gourd, or papier-mâché

- Natural pigments, dyes, and paint

The process typically involves:

- Selecting seasonally appropriate materials (e.g., green leaves for spring, dried grasses for harvest)

- Carving, molding, or weaving the base shape

- Painting or staining with earth or plant-based colors

- Adding decorative elements such as feathers, seeds, or flowers

- Blessing or consecrating the mask in a ritual

Regional differences are significant: African harvest masks feature bold patterns and animal motifs, Asian New Year masks use bright reds and golds, and European winter festival masks may be adorned with fur or horns. Colors are chosen for their symbolic associations — green for growth, yellow for sunlight, white for winter, and blue for water or sky.

For artisan interviews, process videos, and global galleries of seasonal masks, visit toddmasks.com.

Functions and Uses of Seasonal Ceremony Masks

Seasonal Ceremony Masks serve a range of vital functions:

- Ritual and ceremonial use: Central to agricultural festivals, solstice rites, and New Year celebrations.

- Theatrical application: Used in folk plays, dances, and processions to enact seasonal myths or moral stories.

- Festival and holiday use: Worn during Carnival, harvest festivals, mummers’ plays, and contemporary eco-celebrations.

- Modern application: Featured in art installations, environmental education, and cultural heritage events.

Over time, the role of these masks has evolved, often expanding into secular, artistic, or educational contexts as well as retaining their ritual significance.

Regional Variations of Seasonal Ceremony Masks

Seasonal masks reflect the diversity and creativity of world cultures:

- Africa: Bwa and Dogon harvest masks, often large, geometric, and animal-themed.

- Asia: Japanese New Year masks (Otafuku, Tengu), Balinese Barong for rain and fertility, Indian Holi festival masks.

- Europe: Slavic winter masks (Kukeri, Krampus), Swiss Fasnacht masks, and Scandinavian solstice masks.

- Americas: Hopi and Zuni Kachina masks for planting and rain, Guatemalan animal masks for harvest, and Inuit shamanic masks for seasonal hunting rites.

Each region’s masks express local aesthetics, environmental concerns, and mythological narratives, offering a window into how communities understand and honor the passage of time.

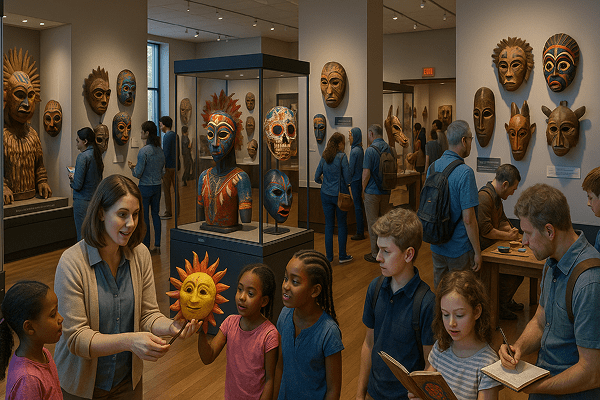

Famous Examples and Notable Collections of Seasonal Ceremony Masks

Many important examples of Seasonal Ceremony Masks are housed in:

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York): African, Native American, and Asian festival masks

- Musée du quai Branly (Paris): Global ceremonial masks

- National Museum of Anthropology (Mexico City): Mexican and Latin American seasonal masks

- Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian (Washington, D.C.)

Private collectors and regional museums also display rare masks used in historic seasonal rites, while contemporary artists create new interpretations. For curated digital galleries and expert commentary, see toddmasks.com.

Influence of Seasonal Ceremony Masks on Art and Culture

Seasonal Ceremony Masks have inspired generations of artists, writers, dancers, and musicians. Their forms and motifs appear in paintings, sculpture, fashion, theater, and film. In literature, seasonal masks symbolize transformation, renewal, and the cycles of nature. In music and performance, they are used to evoke atmosphere, story, and communal emotion.

In contemporary design, seasonal mask imagery influences home decor, eco-art, educational materials, and festival branding. Their ongoing use in public performances and museums helps preserve environmental knowledge and cultural heritage.

Contemporary Status and Preservation of the Seasonal Mask Tradition

Today, the tradition of crafting and using Seasonal Ceremony Masks is alive and evolving. Master artisans, community groups, and cultural organizations keep skills alive through festivals, workshops, and educational programs. Modern innovations include eco-friendly materials, digital fabrication, and collaborations with environmental activists and artists.

Preservation efforts focus on documentation, museum conservation, and intergenerational teaching. Annual festivals and online resources such as toddmasks.com are pivotal for sharing knowledge, connecting communities, and celebrating the living tradition of seasonal masking.

Collecting and Acquiring Seasonal Ceremony Masks

The market for Seasonal Ceremony Masks is dynamic, ranging from affordable artisan pieces to high-value museum artifacts. Authentic masks can be found at art fairs, museum shops, galleries, and online platforms like toddmasks.com. Value depends on:

- Material quality and craftsmanship

- Regional origin and historical context

- Condition, rarity, and documentation

- Artist reputation and provenance

Collectors should seek original, ethically sourced masks, support living artisans, and avoid counterfeits or artifacts of sacred importance to living cultures.