Historical Origin

The concept of oni masks developed through the syncretic melding of native Shinto traditions with imported Buddhist cosmology during the 6th century. The term “oni” (鬼) comes from Chinese characters that originally meant “invisible spirit” or “hidden demon.”

The earliest physical representations appeared during the Heian period, primarily in Buddhist art depicting hell realms. By the Kamakura period (1185-1333), oni had become established characters in religious ceremonies designed to ward off evil and disease.

The masks evolved alongside various theatrical traditions, particularly during the Muromachi period (1336-1573) when Noh theater reached its artistic peak. During this time, mask carvers established distinct styles and schools, with techniques passed down through generations.

Over centuries, oni masks evolved from simple designs to increasingly elaborate creations, with regional variations emerging across Japan. Their function also expanded from purely religious objects to include theatrical usage, festival celebrations, and decorative applications.

Some of the oldest surviving oni masks date from the Kamakura and Muromachi periods, with notable collections housed in the Tokyo National Museum and the Kyoto National Museum.

Cultural Significance and Symbolism

In Japanese culture, oni masks represent a complex duality — simultaneously symbols of evil to be feared and protective entities to be venerated. By donning the mask, a performer symbolically transforms into the oni, temporarily embodying its characteristics and powers.

From a religious perspective, oni masks played important roles in both Shinto and Buddhist practices. In Buddhism, they serve as reminders of karmic retribution. In Shinto practices, oni masks were used in purification rituals where the demon would introduce chaos before being driven away, symbolizing the restoration of harmony.

Numerous Japanese folktales feature oni as central characters, including “Momotarō” (Peach Boy) and “Shuten-dōji.” The legend of “The Red Oni Who Cried” reflects the evolving cultural understanding of oni as complex beings rather than simple embodiments of evil.

Oni masks serve different functions across various social contexts — in theatrical performances, festival ceremonies like Setsubun, and as protective household talismans that paradoxically use the image of the demon to ward off other malevolent forces. Similarly, Kabuki Theatre Masks are used in Japan’s performing arts to portray dramatic characters and evoke strong emotions, highlighting the country’s rich tradition of mask usage in storytelling.

Materials and Production Techniques

Traditional Japanese oni masks are primarily crafted from wood, with Japanese cypress (hinoki) being the preferred choice due to its fine grain, lightweight nature, and resistance to decay. Other materials include paper-mâché, dried gourd, ceramic, metal, and leather.

The production process involves several stages:

- Wood selection and preparation

- Rough carving (arabori) to establish primary forms

- Fine carving (kiribori) to refine details

- Surface smoothing and interior hollowing

- Base coating with gofun (white pigment)

- Painting with traditional pigments

- Lacquering for protection and luster

Traditional tools include various chisels (nomi), carving knives (kogatana), and specialized instruments for interior hollowing.

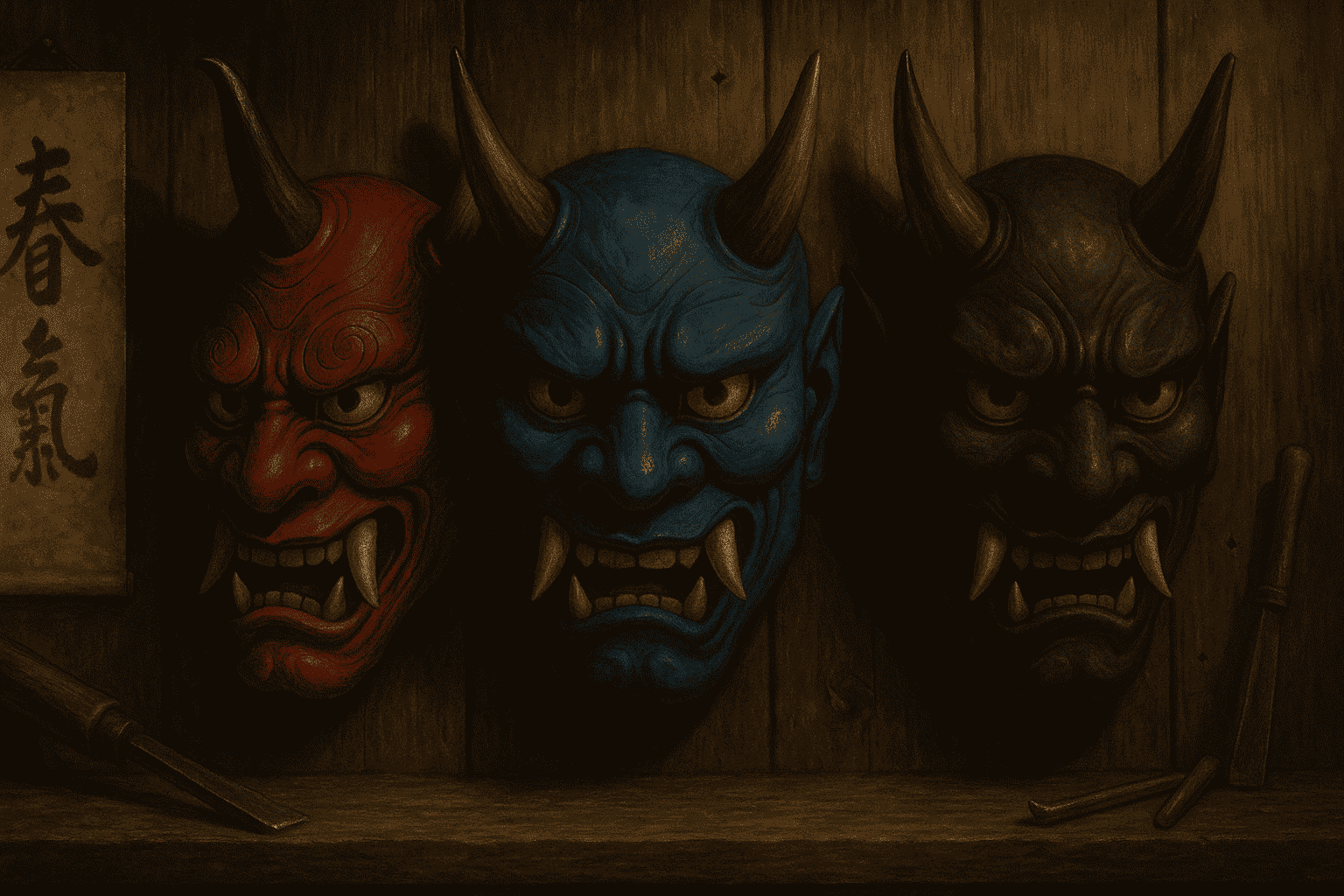

The coloration carries specific symbolic meanings:

- Red (aka): Anger, passion, violence

- Blue (ao): Cunning, sorrow, melancholy

- Black (kuro): Death, unknown, absolute evil

- Gold (kin): Supernatural power, divine authority

Functions and Usage

Oni masks have been integral to numerous Japanese rituals and ceremonies for centuries. During the Setsubun festival on February 3rd, a person wearing an oni mask represents evil spirits while others throw soybeans while chanting “Oni wa soto, fuku wa uchi” (“Demons out, good fortune in”).

In theatrical arts, oni masks appear in:

- Noh Theater: For supernatural characters

- Kyōgen: For comic interpretations of oni

- Kabuki: For certain specialized productions

- Bugaku: Ancient court dance performances

Beyond Setsubun, oni masks appear in numerous festivals including Obon Festival, regional Matsuri celebrations, and New Year rituals.

In contemporary Japan, oni masks serve as traditional performance elements, tourist attractions, decorative art, and motifs in popular culture including anime, manga, video games, and fashion.

Regional Variations

Japan’s diverse geography led to distinct regional styles of oni masks:

- Kyoto Region: Refined masks with elegant proportions and meticulous craftsmanship

- Tohoku Region: Fierce masks with exaggerated features reflecting harsh winter folklore

- Sado Island: Distinctive “Ondeko” (demon drumming) masks with large horns and wide grins

- Namahage Region: Masks with movable jaws worn by straw-caped performers

- Shikoku Island: Stylized interpretations used in “Awa Odori” festival

Japanese oni masks share interesting parallels with demon masks from other cultural traditions, including Chinese Nuo masks, Korean Hahoe masks, Tibetan Buddhist masks, and Southeast Asian demon masks.

Notable Examples and Collections

Several institutions house significant collections of oni masks:

- The Japan Oni Cultural Museum (Ōni no Yakata) in Kyoto Prefecture displays over 800 masks

- Tokyo National Museum houses several designated as Important Cultural Properties

- The British Museum and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston contain notable international collections

- The Ann and Gabriel Barbier-Mueller Collection includes several remarkable oni variants

Influence on Art and Culture

Oni masks have influenced numerous Japanese art forms including ukiyo-e prints, sculpture, painting, tattoo art (irezumi), and ceramics.

Their presence extends across media including literature, film, anime/manga (like “Demon Slayer”), and music. Contemporary designers incorporate oni mask aesthetics into fashion, graphic design, product design, and interior decoration.

As living traditions, oni masks play a vital role in preserving important aspects of Japanese cultural heritage, serving as symbols of community identity and vehicles for cultural exchange.

Contemporary Status and Tradition Preservation

Traditional mask-making continues through established lineages:

- The Deme School: Descended from famous Edo-period mask makers

- The Bidō Tradition: Specializing in Noh theater masks

- Contemporary masters like Kitazawa Hideta and Ichiyu Terai

Preservation methods include traditional apprenticeship, government recognition programs, documentation efforts, museum programs, and festival preservation societies. Modern innovations include using new materials and technologies while maintaining traditional aesthetics.

Collecting and Acquisition

The market for authentic oni masks ranges from antiques ($10,000-50,000) to contemporary master works ($1,000-10,000) and tourist pieces ($100-500). Authentic masks can be acquired through specialized dealers, directly from artisans, at traditional craft markets, museum shops, and auction houses.

Value factors include age, maker’s reputation, condition, artistic merit, regional significance, and ceremonial history. When evaluating authenticity, collectors should examine materials, construction techniques, pigments, weight distribution, and seek expert consultation when necessary.

Ethical collecting practices include ensuring legal compliance with cultural property laws, supporting living traditions by purchasing from contemporary makers, and proper documentation.